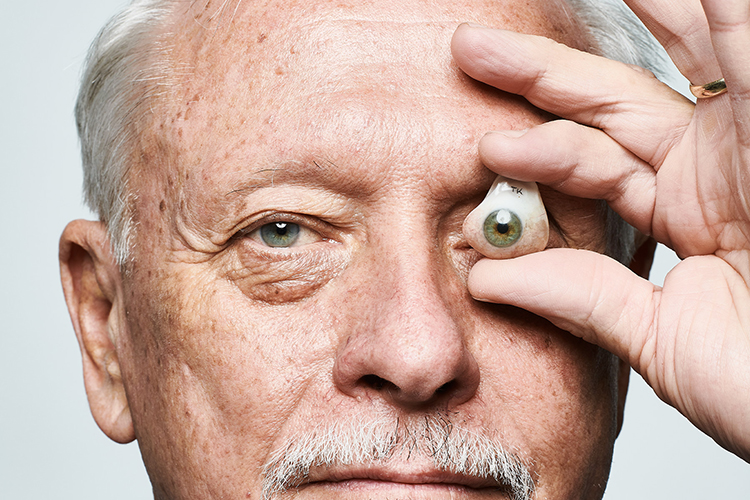

The Man Who Paints Souls

With a brush and empathy, Randy Trawnik creates the world’s best prosthetic eyes

An incredible ocularist and some tough, beautiful Texas women with prosthetic eyes and hands inspired the heroines of We Are All The Same in the Dark and changed my perspective on what “disability” means.

An incredible ocularist and some tough, beautiful Texas women with prosthetic eyes and hands inspired the heroines of We Are All The Same in the Dark and changed my perspective on what “disability” means.

(D Magazine. Photograph by Lavin, ©D Magazine)

By Julia Heaberlin

The pretty little girl saw two things in the mirror that day. A black hole where her eye used to be. And a nurse’s horrified face, reflected behind her.

Even at 9, she knew she was the worst thing the woman had ever seen. Even at 9, she knew to ask herself: “What am I now?”

More than two decades later, she slips into the chair across from me in an Austin restaurant, a fashion model who is confident enough in her beauty that she wears no makeup. Her deep brown eyes are perfect twins.

Not one of her thousands of followers on Instagram, where she models like a beautiful, empowered tiger, or stylists who’ve lined her eyes in black for shoots, or long-ago best friends at an Ivy League university, and certainly no one in this restaurant, know about that night as a kid when her world exploded. She remembers that her mother did not want her to go outside when fireworks began to pop on her grandmother’s Oklahoma property. She remembers feeling oddly lucky that the errant missile was so precise that it didn’t scar her skin—and that the surgeons who worked on her after a frantic trip to the ER were now practiced at traumatic eye injury because of skills newly forged out of the terrorist bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building.

What if the bombing had been later? Or never at all? What if she’d stayed inside like her mother wanted? What if, what if, what if?

Critical eye muscles were saved that night. Because of the way eyes are wired, if the doctors had been too late or not good enough, her other eye could have gone blind in sympathy. But it was a man in Dallas with his own redemptive story who perhaps made her the most whole—who leaned close to her face with a small, white acrylic shell, a brush, and palette of paints, and created a perfectly fitted illusion.

He gave her a secret to keep.

When I began my latest novel, I didn’t expect it to redefine my perceptions of physical beauty and strength. I thought I had no preconceived judgments about human beings who roll into a restaurant in a wheelchair or walk by me with a prosthetic leg. I thought my instinct to feel sorry for their loss and briefly mourn a tragedy of fate meant I was a kind and evolved human being. I even had skin in the game—a foreign object in my own chest, a pacemaker inserted at 27 for a congenital heart condition. Hidden scars. A near-death experience. For years, I’d defy people who thought I should back up and live a lesser life. I fought not to be defined by it.

We Are All the Same in the Dark certainly started out the way all my novels do, with a tiny vision, a dark mood about humanity, and a desire to be authentic. In researching my books, I’ve dug into everything from the Texas death penalty to the trickery of dementia to the use of mitochondrial DNA to identify old and degraded bones.

An imaginary girl with one eye had haunted my mind for three months before I decided to pay attention. I couldn’t see her face in context; I just knew what she was missing. She was evolving, full-bodied in a white dress, blowing dandelions, making wishes. I began to write, to drive her beyond a cliché. I was almost immediately stuck. I thought about drawing in her other eye.

So I consider it fortunate that I didn’t give up on her, that I sent an email into the ether and made a wish of my own—for the Picasso of Eyes to talk to me. I didn’t know until I hit Google, but Randy Trawnik, a world-renowned ocularist, lived a half-hour away from me in Dallas. In the world of eye prosthetics, he was famous and sought after, painting and creating eyes for Saudi Arabian royalty, actresses, models, beauty queens, and athletes.

Isaiah Austin, once one of America’s best college basketball players, used to roam the court with one of Randy’s eyes, adapting, darting, fooling opponents trying to guard a half-blind superhero.

Lauren Scruggs Kennedy, now a New York Times best-selling author and popular lifestyle influencer, wound up in his chair after stepping out of a small plane and straight into a propeller blade, losing both an eye and a hand after a night ride to view holiday lights over North Texas in 2011. At age 23, she shot onto the national news as a miracle survivor, no secrets to keep and a new torch to hold. She struggled back to life in a hospital bed, describing her brain turning back on “like a string of old Christmas lights that sparked and fizzled.”

It took only a 16th of an inch of a whirring blade to tear up her life. What if she’d stepped just a little bit more in one direction or the other? She’d be untouched—or dead.

Trawnik also helps the much less famous, children who are victims of car crashes, guns, abuse, genetic disorders, a stick out of nowhere. Trawnik allows them to maneuver the tribal phase of childhood with a pretty piece of armor. His artistry with a brush—not a 3D printer, not a computer—lets many walk around as anonymously as they like.

My character had a name by now. Angel. She had blown 17 wishes on those dandelions. And they were all the same one.

The girl is cute, casual, easy, wearing her sunglasses under the fluorescent office lights while she waits for me to begin the interview. Rightly, because who am I, a perfect stranger, to see her without her prosthesis, at her most vulnerable? She does not want her name used.

I think I am more nervous than she is. She has worn a prosthetic eye almost since birth.

Trawnik is in a room down the hall, finishing her new replacement eye in his lab. The four-hour journey to his office every few years is an intimate ritual for her and her parents. They eat at the same place for lunch each time, make a day of it, and explain its profound meaning to very few people. Maybe it can’t be explained.

No, the girl tells me, I choose not to tell anyone but my closest friends. People I trust. I wear goggles for sports. It isn’t that hard.

I’m talking to a perfectly regular teenager, tugging out her words. I turn to her mother, carefully monitoring my interview, and ask her to describe her daughter. The words fall out like water.

Tender, resilient, strong, resourceful, kind, empathetic.

I scribble them down. Not regular at all.

Randy Trawnik likes to say that if he does his job right, no one ever knows he was there. And if patients say he doesn’t understand what they are feeling, he reaches in and pulls out his own eye.

Trawnik imagined an ambitious future as an Army officer before the boy beside him in a ROTC exercise shot off a gun too close to his head. Trawnik spiraled, every dream deferred because the military didn’t want a brilliant young man with one eye. He drifted in a local college, pounding the books and the darkness, studying art.

One day, he dropped by his childhood home with a load of laundry. His mother was waiting and wanted a favor. She asked him to walk down the street to comfort the 9-year-old granddaughter of a neighbor who had just lost her eye. The answer from Trawnik was a resounding no.

She is scared, his mother said. That didn’t move Trawnik. A small battle ensued. Finally, she laid it on the line: If you don’t go, I won’t do your laundry.

When he returned, something had shifted for good. He talked to the girl for two hours, starting to heal himself in the process. She would be the first of countless people Trawnik helped put back together because he never strapped on a military uniform and went to war.

Trawnik calls himself an illusionist. He calls his life “providential.” He points out that there are no happy stories sitting in his waiting room. It’s a little war room in itself. But when a patient turns toward the mirror for the first time with a new eye, it is straight out of a movie. Hugs. Tears. For everyone, including him.

I had many things wrong when I began to draw my own one-eyed girl. Prosthetic eyes are not made of glass but acrylic. They are not round but shaped like a giant contact lens and cast to fit each patient’s eye socket. The ocularist is not a doctor but an artist, mixing colors to find the perfect match to nature’s, adding in delicate gold flecks or pale streaks, layering translucent lacquer for a 3D effect. The blood vessels are made of tiny red threads. In Trawnik’s office, it’s a one-day process to cast, paint, and put the eye in place. He believes no one should have to wait a second longer to feel whole. Adjusting to the new lack of depth perception with one eye to shoot a ball, drive a car, fool everyone—completely possible.

And it is perfectly OK to keep a big secret like this, to believe that most people think, like Shakespeare, that the eyes are the windows to the soul. To not want to be defined at first glance by what you are missing. It’s also OK to hope that the idea of physical beauty is evolving. That a missing body part or a jagged scar will someday not be about something lost but simply part of the architecture of a human story.

At 13, Karen Weber was being cautious, glancing right and left down a dark basement hall at a church event for teenagers, afraid a kid would jump out at her. What came flying was a smashed Ping-Pong ball.

What if she had blinked? Turned her head slightly?

Instead, that simple act destroyed her lens. The last thing she saw out of her right eye was a Goldfish cracker streaked with squiggly red lines. Then black.

The eye shriveled, and it was finally removed. When she began ninth grade, she wore a pirate patch while everything healed. She remembers one boy who asked when he passed her in the hall: “Where’s your cat-o’-nine?” referring to a whip. She zinged back: “In my locker.”

What she calls her “teddy bear eye” was the next step up, a cheap prosthesis picked from a drawer of brown eyes, blank and staring, simply the one that matched her other eye best. It fooled no one. Several years later, a boy in the pool flicked that eye with his foot.

What if he hadn’t?

The teddy bear eye was damaged. It had to go. Weber found herself in Trawnik’s chair for the first time. She was 17. He was 26, just beginning.

It is Weber who, decades later, removes her eye and texts me pictures of the bare tissue so I describe it right in my book, who tactfully corrects me on details. She will be the one who laughs a lot, tells me dark, funny jokes, and seems past all bitterness, and I can’t tell that she had any to begin with.

A year after the accident, the boy who threw the Ping-Pong ball into the long shadows walked up to Weber and apologized. She had a crush on him before this happened, which made it worse. The cute boy was standing there, struggling, telling her he was sorry.

It was an accident.

She gave him those four words of forgiveness and never saw the boy again. But Trawnik she saw over and over, for at least 12 more eyes. Forty years after they met, something shifted here, too. They fell in love and married.

Disabled. Disability. Differently abled.

Lauren Scruggs Kennedy hates every one of these labels. “Why can’t we all just be people?” she says. “ ‘Disabled’ puts people in a box. I’ve met many people [with prosthetics] who are much more capable than people with all of their limbs.”

An avid boxer, she says that with one less eye and hand she can do anything she did before other than pound a nail in the wall to hang a picture. When she walked into that propeller blade in Dallas almost nine years ago, Kennedy says, she at first didn’t understand why she was “an inspiration.” Why the Todayshow was calling. Why this fame was happening to her at 23 years old when she was at her most devastated, enduring brain, hand, and eye surgeries. Kennedy became such a media storm that the hospital had to post security.

Trawnik was just as determined to protect her the day he met her at his office, bringing her in for an appointment when no one else was around. She says he understood her emotions in ways others couldn’t. He not only painted her a beautiful matching blue eye, he reassured her that her life had more purpose than ever. He knew.

Today, she uses her platform to deliver a resonant message about a nontoxic lifestyle and the definition of real beauty. Her personal life has spun in a happy direction, too. She married national entertainment journalist Jason Kennedy in 2014, after a chance meeting on the set of E! News, where she was being interviewed about the accident.

Kennedy says that doesn’t mean there still aren’t personal demons to bat away, a “lot of lies in her head” about physical perfection that were established before the accident. It is still sometimes a struggle to feel confident. “Who am I trying to look good for?” she asks herself on those days. Recently, Kennedy tested out her insecurity by walking outside to talk to the man mowing her lawn without her prosthetic arm attached.

She makes it clear: for even the most enlightened cheerleaders for change—and Kennedy is that times 100—the pressure to be the physical stereotype of beauty keeps thumping away. It is this honesty that makes Kennedy, well, so lovely. It is what makes her so appealing to the young girls with lost limbs she is on a mission to help.

In her book Still Lolo, Kennedy writes that it was a child who buoyed her in the beginning. She was speaking to third-graders at a Dallas school not long after her accident. A boy asked to see her bared arm, the one without a hand, which he examined with great interest.

There would be more conversations, more what ifs, in the months of book research that followed my first interview with the girl in the mirror. I was hypnotized by the TED Talk “My 12 Pairs of Legs,” with Aimee Mullins, an athlete, actress, and activist for a more noble and innovative human race. Mullins was born with missing fibula bones and had both legs amputated below the knee when she was just 1.

I’d let her words roll over me at night after a long day of writing: “What does a beautiful woman have to look like? What is a sexy body? … We need to move away from replicating humanness as the aesthetic ideal.” She strolls the stage casually on two stunning legs, pushing a new conversation—that in our blazing high-tech world, wearing prosthetics is not about deficiency and loss but about augmentation and empowerment.

A ferocious heroine began to take shape out of these real-life women—and then a second heroine just as flawed and determined. There was no way for my characters to feel, no single way to be. That was my biggest misconception about wearing a prosthesis. The word “disabled” applies to all of us or none of us.

The characters in this novel would be different from my others and also exactly the same, human beings fighting through terrible dust-ups on our journeys to make us whole. Two years ago, I was signing a book for a woman at the launch for Paper Ghosts, my last thriller. In my talk, I had mentioned the research into prosthetics I was beginning for We Are All the Same in the Dark.

“Is the ocularist you were talking about Randy Trawnik?” the woman asked.

I looked up from signing, surprised, straight into striking eyes. “Yes. Do you know him?”

She winked.